American Ingenuity = American Prosperity

The Founders’ decision to foster non-practicing entities and patent licensing proved crucial to America’s rapid technological progress and economic growth. Patent records from the nineteenth century reveal that more than two-thirds of all the great inventors of the Industrial Revolution, including Thomas Edison and Elias Howe, were non-practicing entities who focused on invention and licensed some or all of their patents to others to develop into new products. |

Washington and Lincoln on Patent Protection

|

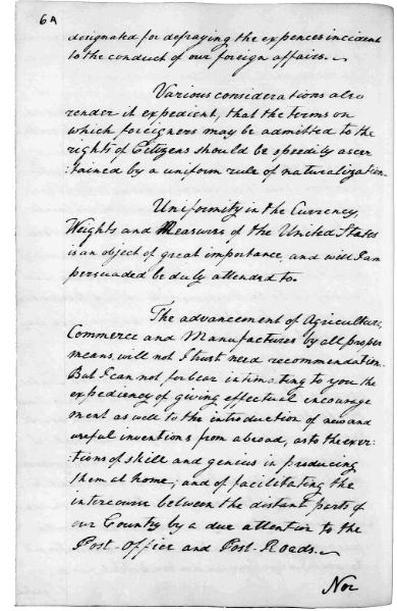

George Washington, in the First State of the Union Address, Urges Congress to Pass Laws Protecting Patents:

The advancement of agriculture, commerce, and manufactures by all proper means will not, I trust, need recommendation; but I can not forbear intimating to you the expediency of giving effectual encouragement as well to the introduction of new and useful inventions from abroad as to the exertions of skill and genius in producing them at home, and of facilitating the intercourse between the distant parts of our country by a due attention to the post-office and post-roads. |

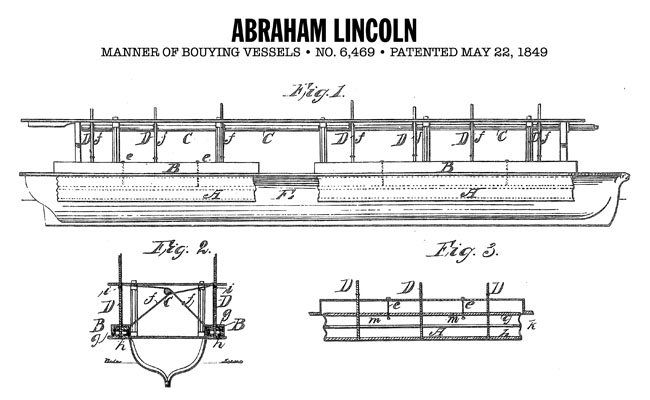

Abraham Lincoln on Patent Protection: [I]n the world’s history, certain inventions and discoveries occurred, of peculiar value, on account of their great efficiency in facilitating all other inventions and discoveries. Of these were the arts of writing and of printing, the discovery of America, and the introduction of Patent laws. [T]he patent laws...began in England in 1624, and in this country with the adoption of our Constitution. Before then any man [might] instantly use what another man had invented, so that the inventor had no special advantage from his own invention. The patent system changed this, secured to the inventor for a limited time exclusive use of his inventions, and thereby added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius in the discovery and production of new and useful things. |